Presidents and the Labor Movement: A History of Conflict and Progress

Presidents’ Day is often filled with conversation about leadership and legacy. But for working people, the presidency is measured less in monuments and more in paychecks, safety rules, and the right to stand together on the job. Across industries and communities, the occupant of the White House shapes whether workers have real power—or whether that power is steadily stripped away and handed to wealthy interests and corporate executives. The last thirteen months have made that reality impossible to ignore, as presidential power has once again been used to favor corporate interests over working families.

The Era of Federal Strikebreaking (1870s–1900)

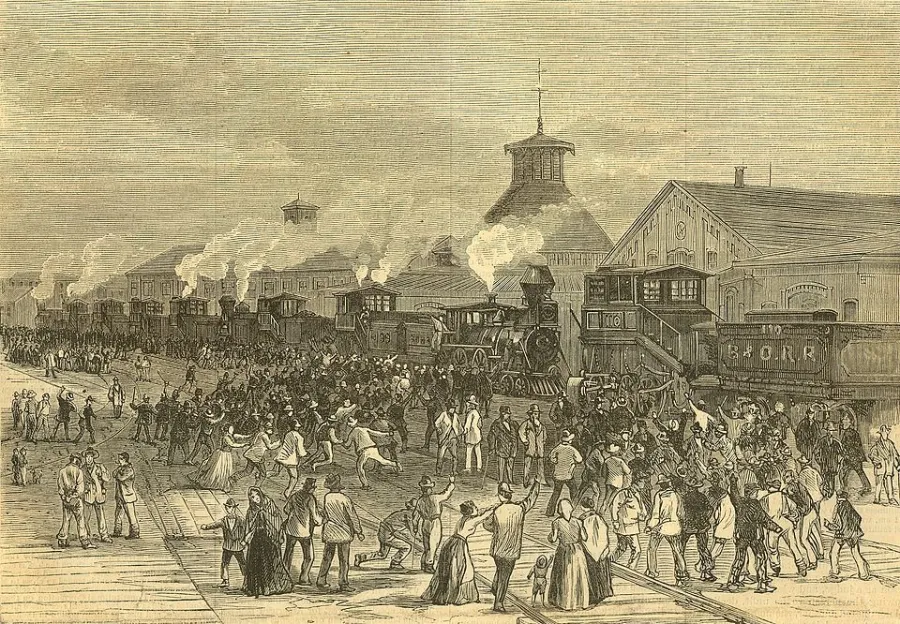

During the rise of industrial capitalism in the late 19th century, the federal government functioned primarily as an enforcer for industrial capital—actively suppressing labor. Presidents like Rutherford B. Hayes set a grim precedent during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, deploying federal troops to crush uprisings over wage cuts. This era reached its peak under Grover Cleveland, who during the 1894 Pullman Strike, bypassed state governors to send federal troops into Chicago. More importantly, his administration secured the first "labor injunction"—a court order that criminalized strike activity. This established a precedent where the judiciary and the executive branch worked in tandem to treat union organizing as an illegal conspiracy.

The Shift Toward Mediation and Rights (1901–1921)

The narrative began to shift with Theodore Roosevelt. During the 1902 Anthracite Coal Strike, Roosevelt broke from tradition by refusing to act as a corporate enforcer. Instead of automatically deploying the military to assist mine owners, Roosevelt threatened to seize the mines if owners refused to negotiate, forcing the first federal arbitration between capital and labor. This momentum grew under Woodrow Wilson, who elevated the Department of Labor to cabinet status and signed the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, famously referred to as labor’s "Magna Carta" for its attempts to protect unions from being treated as illegal conspiracies. Section 6 of the law declared that "the labor of a human being is not a commodity or article of commerce," exempting unions from the antitrust laws previously used to break them. Wilson also signed the Adamson Act (1916), which established the first federally mandated eight-hour workday for interstate railroad employees.

The New Deal and the Rise of the Middle Class (1933–1969)

The most transformative era for American workers arrived with Franklin D. Roosevelt. Through the New Deal, Roosevelt fundamentally rewrote the social contract. The Wagner Act (1935) created the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and federally protected the right to organize. This was followed by the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which established the first national minimum wage (25 cents an hour), mandated overtime pay, and strictly prohibited oppressive child labor.

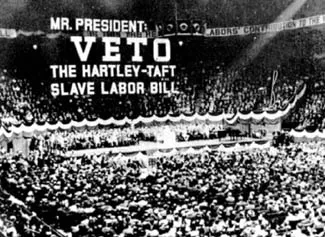

Harry S. Truman expanded this legacy by using the executive branch to drive social change, most notably through Executive Order 9981, which abolished racial discrimination in the United States Armed Forces and led to the eventual desegregation of the federal workforce. However, Truman also faced the most significant legislative rollback of the era: the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947. Truman issued a stinging veto, calling it a "slave-labor bill" that would dangerously weaken unions, but a conservative Congress overrode his veto, legalizing "right-to-work" laws that persist today.

Later, Lyndon B. Johnson tied economic justice to civil rights, proving through the Great Society that workplace protections and social equality were inseparable. Even Richard Nixon, despite his conservative leanings, signed the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) of 1970, creating the first federal agency dedicated to workplace inspections and hazard prevention.

The Turning Point and the Globalized Economy (1981–2001)

The trajectory of labor rights took a sharp turn with Ronald Reagan. In 1981, Reagan invoked the Taft-Hartley Act to fire 11,345 striking air traffic controllers (PATCO), permanently replacing them and effectively signaling the end of the federal government’s role as a protector of strikers. This era saw a sharp decline in union density and a rise in income inequality. While Bill Clinton introduced the Family and Medical Leave Act, his legacy remains complicated by trade agreements like NAFTA, which led to rapid outsourcing of unionized manufacturing jobs. many labor advocates argue accelerated deindustrialization and weakened the bargaining power of manufacturing workers.

The Modern Conflict (2009–Present)

The 21st century has seen a widening divide between Democratic and Republican approaches to labor. Barack Obama strengthened overtime protections, appointed pro-worker leaders to the National Labor Relations Board, and signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, making it easier for workers to challenge pay discrimination. Joe Biden became the most openly pro-union president in generations—most notably as the first sitting president to join workers on a picket line. His administration appointed Jennifer Abruzzo as NLRB General Counsel, who led the landmark Cemex decision, requiring employers to recognize unions when they commit unfair labor practices during organizing campaigns. Biden also signed Executive Order 14026, raising the minimum wage for federal contractors to $15 an hour and indexing it to inflation.

Through the American Rescue Plan, Biden signed the Butch Lewis Act, delivering a historic federal rescue of multiemployer pension plans and securing the retirements of millions of union workers. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act further strengthened labor standards by requiring prevailing wages and encouraging the use of union apprenticeship programs. In addition, Executive Order 14063 mandated Project Labor Agreements on large federal construction projects over $35 million, ensuring they are built by union labor.

In sharp contrast, Donald Trump’s two terms have focused on deregulation and the systematic weakening of organized labor’s infrastructure. His first term was marked by regulatory rollbacks, weakened safety standards, and judicial appointments that undermined public-sector unions. In the first year of his second term, this agenda has intensified through a series of structural shifts designed to tilt the balance of power further toward employers. The current administration has worked to weaken the National Labor Relations Board by promoting employer-friendly rulings that make it harder for gig and contract workers to organize. It has pursued federal deregulation by rolling back prevailing wage protections and moving to eliminate collective bargaining rights for federal employees through executive action. At the same time, judicial appointments favoring the “major questions doctrine” have been used to limit federal authority over overtime eligibility and workplace safety, further eroding long-standing worker protections. Together, these policies encourage worker misclassification, reduce access to benefits, and weaken enforcement of labor standards.

Conclusion

From the bayonets of the Gilded Age to the picket lines of the 21st century, the American presidency has never been a neutral force in the struggle for workers’ rights. The history of the presidency is inseparable from the history of the American workplace. Whether through the creation of the 40-hour workweek or the mass firing of strikers, presidential actions shape the power of working people. As we look toward the remainder of 2026, workers once again face renewed obstacles to organizing, bargaining, and maintaining safe conditions. History reminds us that progress is never guaranteed. It is a hard-won series of victories that must be defended by every generation. This Presidents’ Day, we are reminded that the true measure of leadership lies in whether a president stands with the people who keep this country running—or works to dismantle the institutions that protect them.